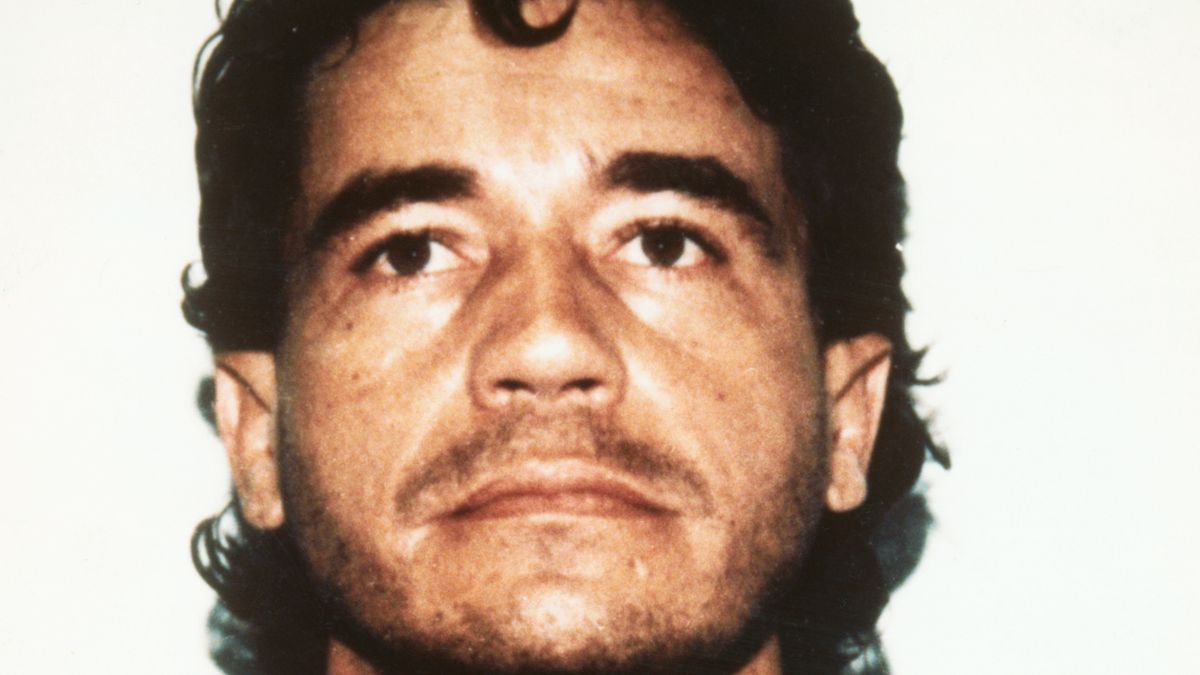

Alarm bells went off not only for me but for several colleagues and agencies Jan. 7. The reason for this is a video that appears online, in which Stefan Huijboom anxiously recounts his fear of being arrested because he had asked questions about Hezbollah to the Ministry of Defense in Beirut a few days earlier. And indeed: he is arrested. Behind the scenes, a handful of colleagues and agencies begin a rescue plan, but the reason for Stefan's arrest later turns out to have absolutely nothing to do with journalism.

Stuck in a Lebanese cell

Stefan and I are sitting in a café just off the Red Light District in Amsterdam; he looks tired, confused and anxious. The night before, Stefan landed at Schiphol Airport after being held in a Lebanese cell for seven days. 'Michel, you won't believe the conditions there. There are twice as many prisoners as beds and they cram thirty of you into a small cage. There's screaming, it was terrifying.'

As Stefan tells his story, I think he is lucky. For the same money or a little less, they would have kept him there for an extended period of time. Somehow, he has escaped (again), although chances are that the price for his earlier lies will cost him dearly afterwards.

Persona non grata

A few weeks earlier, Stefan left for Lebanon, the country where he will now be persona non grata for the rest of his life. He was tired for a while of Kiev and Moscow, from where he writes as a correspondent for Reporters Online and Geenstijl, among others, and was looking for a new challenge. Soon after arriving in Beirut, Stefan began picking up the pen to write again. Critical as ever, but in a country he does not know, with a language he does not speak.

Michel, I'm in the shit

On January 7, I get a message from Stefan via Facebook 'Michel, am in Beirut and I'm in the shit. Hotel room searched by police this morning. Why I don't know. Maybe bugged. Asked questions of the Ministry of Defense a week or so ago about foreigners fighting alongside Hezbollah.' I advise him to go to the embassy and inform some colleagues. Later that day he reports that the embassy, where he made an appointment, cancelled an hour in advance. 'Embassy calls. My case is not a priority, so come back tomorrow. Wtf!!!'

The next day at 9:00 Stefan has to report to the police. In the evening, Stefan still asks me to share his Facebook message, in which he tells the world that he fears being followed by asking critical questions and fears being arrested.

Under the radar

The next morning Stefan goes to the police, in a response to a public Facebook message he still lets them know that his 9:00 a.m. appointment has been moved to 11:00 a.m. 'What a terrible monkey country this is saying, "just come back at 11."' After that, there is silence. Both publicly and privately, he no longer responds to messages. Behind the scenes, the wheels begin to move. The embassy, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Dutch Association of Journalists and colleagues begin to look into Stefan's fate. Little by little information is coming in, chat groups are being set up and other journalists - some of whom are in the region - are asking via private messages if there is anything else they can do. On Twitter, things remain glacially quiet, and everything remains under the radar.

The following days become more and more confusing for outsiders, stories of espionage are circulating, and Stefan's orientation is also cause for concern. For a moment it begins to seem to me that the online silence surrounding his arrest is intended to increase the chances of a diplomatic solution. Through one of his clients in the Netherlands I understand that they are serious about it, "Other than that, we are maintaining radio silence. I decide to stand back.

This has nothing to do with journalism

The following days remain silent online; even on Stefan's accounts, more and more concerned colleagues begin to distance themselves from the case. 'This has nothing to do with journalism,' and even his mother, with whom he maintains a poor relationship, expresses herself on Facebook. 'I know, but I'm not allowed to say anything.' Privately, I get a message from his mother. 'It's too bad still have to process it myself. Love that you are busy with him, but one thing he lies about everything. Bye

The lies

As Stefan takes a sip of his chocolate milk he looks outside, in the café near the Red Light District in Amsterdam some new people are coming in. 'It was so enormously expensive Michel, not normal. I found out that it wouldn't be long before I wouldn't have a penny left. In the hostel where I was staying a safe was open, in it was someone else's wallet, I then took pictures of his credit card. When I was finally really broke I used those credit card details to pay for a hotel. That went well twice, the third time it stopped working.' The total amount involved was $800. 'I knew it was wrong and that the police were after me. People from the hostel and the credit card owner started adding me on Facebook, which told me enough. I thought, if I throw it on journalism, then I might get easier help to get out of the country, I was desperate Michel. Then I approached you too, and later I spread a video on Facebook that I was afraid I was being followed by the police after asking questions and that they had searched my hotel room.' In reality, it turns out later, Stefan was still walking free at the time we thought he had been arrested. 'I had turned off my Facebook for a day.' Later, when Stefan did get arrested, most people still don't know anything about what really happened.

Shame

Embarrassed, Stefan says staring at the table. "What have I done? Many colleagues are angry with me, and what are clients going to say? The Dutch Association of Journalists wants nothing more to do with me.'

According to Stefan, the $800 Stefan had charged to his credit card was repaid, under the watchful eye of the Dutch embassy, by a Dutchman who was in Beirut; the trip back to the Netherlands was paid for by a client.

'I am extremely embarrassed in front of colleagues who have worked for me. Some of them have let me know that they are not yet ready to sit down with me. It has yet to sink in. I am very keen to talk about it. It is now a burden I will carry with me to Ukraine.

'I saw no way out Michel, I thought this was my only option to get out of the country...'