I am not quite sure what I will find when I step into the central square of the refugee camp early in the morning, past the overflowing garbage containers. Today I am following Dutch photographer Niels Wenstedt, who is here to do a photo shoot for Hollandse Hoogte. Together with a Red Cross contact, we just passed through the lightly guarded main entrance. On our way to an introductory meeting with the shelter's acting manager, Ognyan.

The refugee camp we visit today is one of three refugee camps around Sofia, Bulgaria's capital. The three-story property is moderately maintained on the outside, the fences creating a fence for a dilapidated playground used as a laundry rack and trash lies all over the grounds. From the first step on the grounds, you can feel the tense atmosphere that exists. Where at first I thought this one was a hostile one, I later learn that this is desperation.

The stench of feces

Ognyan, the deputy manager of Voenna Rampa, looks sullen as we enter his office. Like an overwrought prison warden, he discusses his frustration at our arrival with our interpreter. What exactly is bothering him I will never know, but after receiving some facts and rules of the camp, our tour can begin. Like a watchdog, Ognyan accompanies us.

The condition of the building, which houses 800 refugees, is poor. Broken ceiling tiles, smashed walls and a constant stench of garbage and feces fill the corridors of the complex. In the first moments of our stay, it is mainly distrustful eyes that follow our tour of the building; it is only later in the day that the distrust turns into despair and I am overwhelmed by hellish stories of flight, horror and uncertainty.

This conversation has consequences

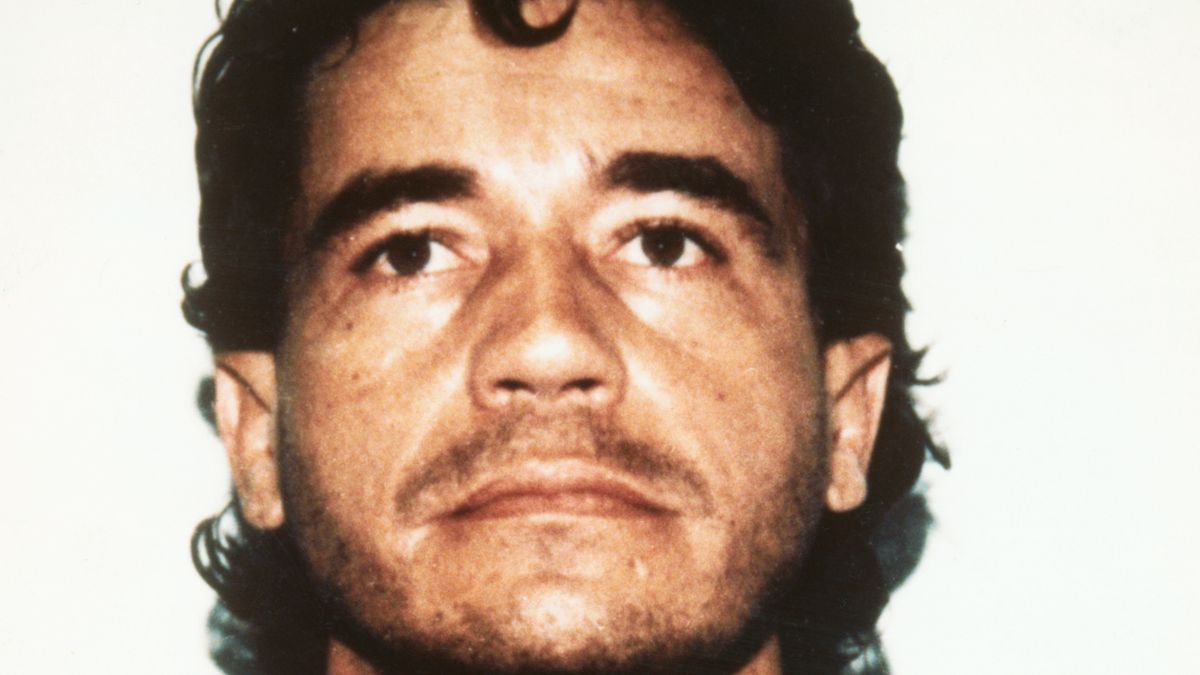

If I Sirwan I probably would have avoided eye contact and bowed to him. The muscular Iraqi who resides illegally in the refugee camp looks at me piercingly as I walk into his little room, which he has to share with 3 others. The cooking is primitive on a single stove behind me and the corridor in front of his room soon fills up with children and their parents, who begin to notice that there are suddenly strangers in the house.

Sirwan is scared, he tells me about the atrocities he has encountered along the way, the times he has been beaten up by Bulgarian police, and the fear of going outside the camp because he feels he may be targeted by local residents there as well. 'I am afraid our conversation will have dire consequences for me,' Sirwan says to me as he gestures to the interim manager Ognyan. Secretly, I share contact information with him and later today I will learn via the Telegram app that our conversation so far has had no negative consequences.

Sirwan is negative about a lot, about the shelter itself, the food, the care and mainly the lack of clarity. He told me that even a temporary refugee identification has not yet been issued to him. Ognyan, who overheard our conversation, later tries to disprove it. 'He really did have an ID, I gave it to him myself. The problem is that they sell those IDs for 20 euros in downtown Sofia and then come back here and say they lost it, that way I can keep busy taking passport photos'

What I am not allowed to see

As my conversation with Sirwan comes to an end, several people standing in the hallway try to get my attention. Children because they perk up when they see a camera, but mostly parents who want to show me the real misery. The floor in the hallway where we stand is filthy, half the boards in the ceiling are gone and the light dangles weakly shining from a wire from the ceiling. The walls full of holes are chalked with texts and signs. People try to tell me that there are rooms where 20 men lie in a room, that even the hallways are littered with mattresses to create sleeping spaces, and that the bathrooms are a disaster. They try to show it, but Ognyan won't. He simply does not allow it and would rather we go see the kitchen. Pictures I receive later confirm why. That part of the property, the bathrooms, is one big disaster

Grandma Fatima misses her family

Fatima (84) sits disconsolately on the tip of her loft bed as she shares her story. Fatima fled Afghanistan with her family and was found along the way in a forest in Bulgaria and separated from her family. Strangers have now sort of adopted her in this refugee camp, she has no idea where the rest of her family is, possibly they are in Germany and Austria.

No drugs

He has been working here as a doctor in Voenna Rampa for three years now. 'Some days I treat as many as 60 patients, but we have a problem. I am out of medicine again, many ailments I cannot treat'. Earlier I learned in a conversation with our Red Cross contact person that money is not the problem 'The European Union made over 4 million available last year, among other things for medicines, but there is a lawsuit pending about the tender of the supplier of these medicines, and as long as that lawsuit is pending, the money is frozen and we can't do anything with it'. During the day, I encounter many children with rashes, young people with inflammations and people with chronic conditions who cannot be helped at the moment. 'If it gets out of hand, we can have people with life-threatening conditions transferred to a hospital' the doctor says apologetically to me.

A garbage dump

When lunch is over I go outside to have a smoke and take a walk around. The ground is studded with plastic cups in which lunch was handed out earlier today. It seems like everyone collectively wants to make it one big garbage dump. Our Red Cross contact tells me all the things they are doing to educate people in other camps. What they tell them to do better with hygiene. 'Every day we give one-on-one lessons there with products and situations, but even there it doesn't seem to be catching on yet'

As I walk around the building and there is commotion a little further on as people from inside the building, shouting at Niels, try to make it clear that the pile of garbage under their window is demeaning, I get into a conversation with a couple of guys who are on a makeshift campfire are making a canned meal. Again I hear the stories of beatings and robberies by Bulgarian police. 'In Serbia none of that happens, the police there are nice, here we are afraid to walk out of the gate.'

A flood of refugees we cannot handle

'At the moment, I think Bulgaria is hosting over 5,000 refugees, very much larger is our capacity here as well,' says our Red Cross contact. 'If we try very hard, we might be able to accommodate 15,000 people, but we can't handle a larger influx of refugees.' A day before my visit, it was announced that the European Union is giving Bulgaria more than 100 million euros to strengthen border security and accommodate more refugees in the future. In recent weeks, Turkey threatened to reverse its refugee deal with Europe. This could mean easier passage to Europe for the three million refugees currently in Turkey.

Outside, children are playing; as soon as they see Niels' camera, a smile On their faces. As if problems don't exist. 21-year-old Guldar from northern Syria stares ahead as she tells us about her dreams, one day she would like to become a journalist. She has been in a camp in Bulgaria for six weeks. Almost everyone I speak to, like Guldar, has a dream, but currently feels hopelessly trapped in a country where none of them actually want to be. 'People hate us here.

Over 200 illegals in the camp

Yesterday there was a check in the camp. Other than the original residents, over 200 people were found to be staying illegally or actually should be in another camp. By buses they were dispersed, back to their original camp, or to the detention center for an initial intake.

You can see the entire photo reportage by Niels Wenstedt for Hollandse Hoogte. here retrieve