How a boy of 27 manages to bring hope to a place where people are losing their dreams for the future.

It has rained just before I walk onto the grounds of "the Jungle" with a delegation of people. The illegal tent camp near the gates of Calais is on the verge of evacuation. During a visit to the camp on Sept. 24, French President Hollande called for its complete dismantling. Nearly 10,000 residents will be redistributed to 164 reception sites across France, according to the president. The evacuation, scheduled for two days after our visit, was postponed at the last minute for at least a week. The uncertainty among the residents of "the Jungle" remains.

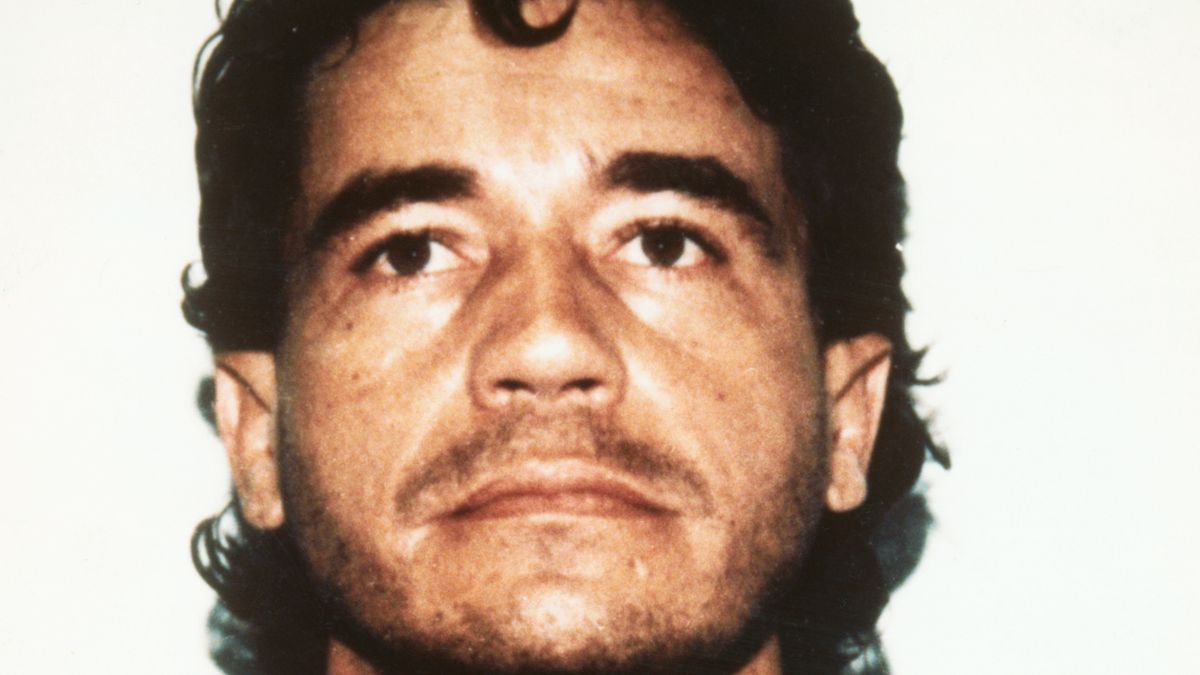

Zimako Jones

If eyes could speak, Zimako Jones' dark eyes speak of an eventful and hard life. The 27-year-old Nigerian refugee has been in the illegal refugee camp "the Jungle" in Calais for more than a year. Unlike most of the temporary residents, he is not there to find his way to England; Zimako wants to stay in France.

He fled Nigeria with his parents after the 2011 presidential election. His Togolese father who worked for the previous government was threatened. After spending three months in Libya, Zimako lived in Italy for 2 years. He then traveled on to France. After wanderings, he finally ended up at "the Jungle" in Calais in April 2015. He does not like the name, preferring to speak of the Forum of Calais.

Animals belong in 'the Jungle,' humans do not

I am traveling today with a delegation from the Netherlands, including Johan from the Wood, county administrator and member of the Council of Europe, the European body that has human rights and refugees as its core tasks and is the boss of the European Court of Human Rights. In addition, representatives of the NGO Portagora and Refugee Council Netherlands join us. Zimako is our contact in "the Jungle" today.

'The Jungle' always looks sad , but today it is even worse. The rains of the morning have turned the dirt roads into muddy paths, and the plastic sheeting that serves as a canopy of plywood "houses" hangs half-knotted together. It is Saturday and 'the Jungle' is teeming with volunteers, mostly English. In recent years, 'the Jungle' has developed more and more into a self-contained neighborhood, with all its amenities. One that you might find in the suburb of a big city in an underdeveloped country, though, and which we would label as a slum. Zimako seems to see this differently, and I notice more and more that this purebred optimist keeps looking at the positive things.

That respect comes for a reason

Zimako is respected within "the Jungle" and not only by Nigerians. He is talked to a lot by everyone and always in a positive way. He does not stand still and he is always busy. That respect comes for a reason, he has earned it in the relatively short time he has been here. And not only the respect, also the trust of many of the temporary residents of "the Jungle.

When Zimako was expelled from another camp by the government in early 2015 and ended up in "the Jungle," he quickly decided that something had to change, "We can't wait for the government, here we have to do it ourselves," he says in an interview with the BBC. Zimako, who he says never had a hammer in his hands at home, decided to build a school on his own. 'I learned here what powerful things you can do with this,' referring to the hammer. 'People speak many different languages here, French can become a language to communicate together, a language for brotherhood, that's why I built the school.'

Trust

From April through July 2015, Zimako built the school with materials he could find left and right on the property. This did not go entirely without a hitch. For example, halfway through construction, a major fight between the camp's Afghan and Sudanese residents ensued. During this fighting, they looted much of his construction material to fight with. But he did not give up and continued building stubbornly when peace returned to the camp for a while. In the months that followed he received more and more help. Three months after construction began, three hundred people gathered in July 2015 for the official opening of his school.

"Everyone in the camp trusts me, I don't need the trust of the government," Zimako states in a BBC interview, yet he is being trusted by the government. For example, he has been in talks with the Minister of Education and teachers at the school have been recognized by the Ministry of Education. Zimako's school is also more than a language institute. Every day there, with the help of volunteers, between 20 and 50 adults and children receive various lessons. The school also serves as a liaison with other organizations and even the government.

Thus, all the Islamic associations in the camp, the Catholics, NGOs and even the police have signed a kind of covenant recognizing the school as a public place. So during the evacuation of part of 'the Jungle' earlier this year, the school was spared, it now stands almost a kilometer away from where the rest of 'the Jungle' continues. 'If the government would trust me completely and give me money, I will change the whole jungle in 3 months'.

The anarchy

Unfortunately, the fraternization you see in and around the school is far from the rest of "the Jungle. Mutual quarrels and confrontations with the police determine the order of the day. Police tear gas and stabbings have become normal fare. Many of the people in "the Jungle" have been here for months, sometimes years, and more people arrive daily than leave. Over 1,000 children live in the camp; an estimated 800 are alone and unsupervised.

Children are mostly left to fend for themselves and the most terrible stories are coming in left and right. Children who are raped or even go missing, children who fall into the hands of human traffickers or one of the drug rings within the camp. Marc Dullaert, former children's ombudsman of the Netherlands who recently visited the camp, expressed his concerns in a broadcast of Kruispunt. 'They are the gates of hell, a few hours travel from the Netherlands. We should not want this, this must be solved for those children, that is step one, period.

A school alone is not enough

It is not only the school that keeps Zimako busy. Last year, for example, he also fought for better facilities in the camp, and not without success. Working with a lawyer, he got better facilities done. Especially electricity and water.

Also, the next project is already in its infancy, a laundromat. Zimako does not believe that when the camp is going to be cleared one of these days, all the refugees will actually disappear. 'Right now there are no facilities for people at the camp to wash their clothes. When people will soon be living scattered through the area on the streets, this will be no different'. The beginnings of his laundromat are already there. Near the camp, Zimako has managed to rent a space with the help of donations from the Netherlands. From there, he plans to offer a laundry service to refugees in the region in the future.

London... Calling

As we stand with a group at the edge of the camp in the late afternoon, less than 20 meters away from the police we see dozens of people running in small groups through an opening of a hedge across the street. Already on their way to find an entrance to the fence-fenced highways. Hoping today to be lucky enough to find an illegal elevator towards their dreamland, England.

Even for those who do not want to go to England, "the Jungle" is for now one of the few places they can call home. Application for asylum is a slow process in France and it can take months, if not longer. As we drive away from the camp, night falls. Later, I will learn via Twitter that there was another hour-long brawl between police and refugees after we left. For now, the more than 10,000 refugees can stay in "the Jungle," but the uncertainty about the upcoming evacuation remains.