Our fixer Cheo runs back and forth to the gate of the prison while Joris and I sit just down the street waiting anxiously on the hood of our car. A daily market develops on the street outside the prison; it is a coming and going of visitors and vendors at the gate of Venezuela's most notorious prison.

Yesterday, When we visited the prison, not everything went as planned. It was not the first time we visited the Tocoron prison. While we were convinced that everyone was properly bribed before we entered the prison, all of our equipment was confiscated by the national guards guarding the outside of the prison. When we left the prison, we did not get our equipment back. Later that evening, after some conversations between our fixer and some prisoners, we were told that the inmates' boss had taken our things from the Guardia National and that we could get them back at the prison gate.

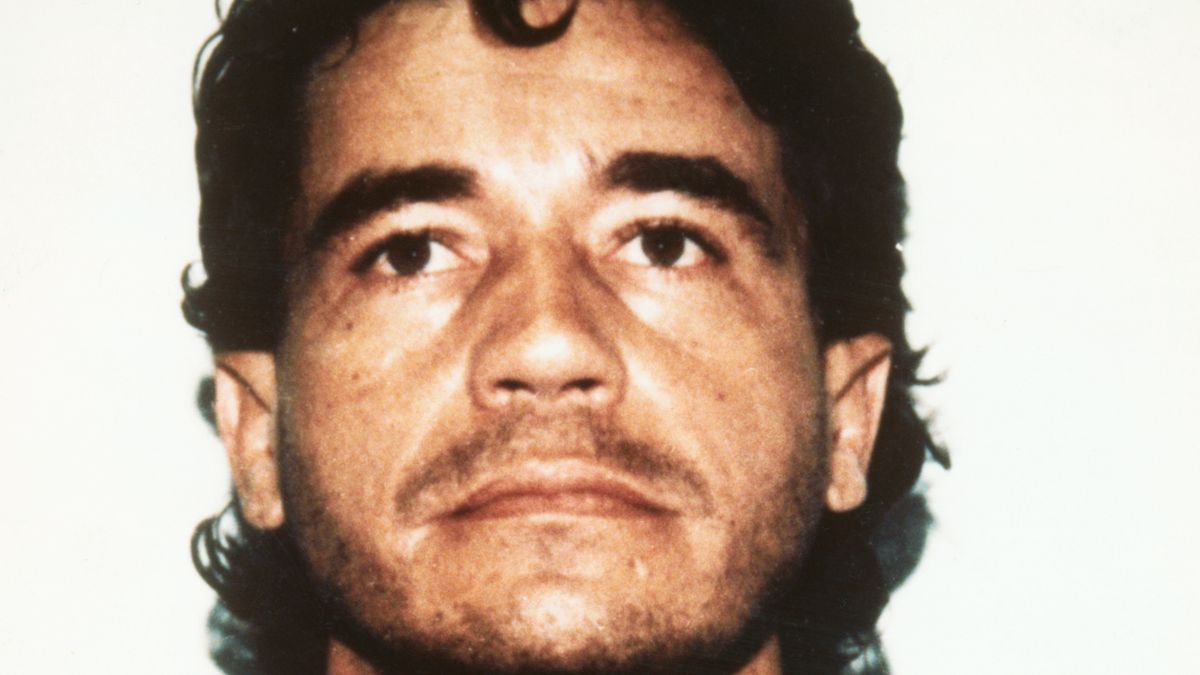

Tocoron, a prison for 750 inmates was built in 1982. Today it holds 7,500 prisoners. Guards and government personnel are not welcome in this prison run by prisoners. Chief among them is inmate Hector Guerrero Flores aka Niño Guerrero (The Warrior Child). The ruthless leader has two faces. While he runs his prison and his criminal empire with an iron fist, he is otherwise known as a benefactor. He lifts families out of poverty and gives wheelchairs and medicine to those in need. Niño Guerrero not only runs the Tocoron prison, but his former residential neighborhood of 28,000 residents is completely under the control of Niño and his men. Many others tell us that his power goes even much further in Venezuela.

In recent years, Niño has transformed his prison into a small town where nothing is missing. As we walked through the prison, we saw a swimming pool, a zoo and a disco. On the main street are restaurants, stores and amenities such as a bank, a television provider and gambling houses. Niño and his armed friends ride around the crowded prison on motorcycles undisturbed.

After an hour and a half of waiting in front of the prison, there is rescue. One of Niño's henchmen walks out of the front gate of the prison with our shoulder bag. When we open it, we see that all our equipment is still in it and wonder how much this prank has cost us? Nothing, courtesy of Niño .

Relieved, we continue on our way to Venezuela's capital, Caracas . A mass demonstration is planned there today. For years there has been unrest in the corrupt country ravaged by an economic crisis. In previous demonstrations we visited in recent weeks, there were clashes between protesters and authorities. So far, 43 protesters have been killed in these clashes.

When we arrived in Caracas, we exchanged our car for motorcycles. Because of the protests, there was almost no other way to get through the congested streets of the capital. Once we arrived at one of the highways serving as the route for today's demonstration, we saw that the first protesters were already preparing for what was to come. Logs are being dragged across the road, fences and anything else they can find are being used for the first barricades. In the distance, we see the first clouds of smoke from tear gas coming our way. In the hours that follow, a battle erupts between the authorities and the protesters, and the protesters are gradually forced to move into the center of the city.

While there is no money to import food into Venezuela, there is no shortage of tear gas canisters, which are sometimes shot at protesters by the dozens. As night begins to fall, the mood grows grimmer. As Joris and I make our way to our car, we witness the first car fires, stores and offices being looted. As the protesters continue their struggle, a new demonstration is announced on social media for the next day. Joris and I continue toward our next stop, the city of Maracay.

Axel (23) holds open a refrigerator to show its contents. He lives with his brother Billy (27) and mother Glenda (55) and father Rosvelt (60) in a middle-class neighborhood of Maracay. At the kitchen table, the family talks about the effects of the crisis.

Glenda worked as a bioanalyst at the hospital for 20 years. Since yesterday, her minimum wage has more than doubled to 105,000 bolivares. That is equal to $18. Until yesterday, her full-time job earned her less than $9 a month. The father of the family has been a merchant all his life, a job that today, with the complete collapse of imports, is almost impossible: "Nowadays the only merchant in the country is the government, but I trade in clothes. There is no trade for me now."

The family has lived together for 22 years in a safe middle-class neighborhood in Maracay. The father explains to us that the neighborhood has changed in recent years. "People with money used to live here. When the crisis got worse, many of our neighbors left. The government expropriated many of the houses in this neighborhood and gave them to "government-related people," people with almost no income, sometimes no job, no education. They don't maintain their belongings, don't care about the neighborhood and have no respect." "We used to be able to talk to our friends and family about politics in Venezuela, that subject is too sensitive now."

"We don't have money for the car or the house anymore. All the money we have, we spend on food and medicine, it's too expensive." From his closet, Rosvelt pulls out a strip of medicine. "Take this for example. This strip of 14 pills, enough for a week, costs 25,000 bolivares in Venezuela." In his other hand, he holds a box. "This box, with 300 of the same pills...., and enough for five months, costs me 55,000 bolivars in Colombia."

"I suffer daily when I work in the hospital. It is terrible not being able to give people the help they need because of the shortages of medicine and medical equipment. The government watches but does nothing to change the situation," continued an emotional Glenda. "Every day people die unnecessarily, people stay sick unnecessarily. The government is more concerned about their image. All hospital employees are required to participate in pro-government demonstrations and the government spends a lot of money on propaganda materials.

"A shortage of food and rising inflation have forced people to queue for hours at the supermarket every day in the hope of getting basic items like bread, rice and milk. Food prices are rising daily, and for a simple lunch on the side of the road you easily pay 7,000 bolivares. With luck, you can find a pack of pasta for 4500 bolivares, which is more than a day's wage.

Before yesterday's 60% pay raise, Glenda, the sole breadwinner of the house, earned 48,000 bolivars a month. How can you live with that? "Little by little, any money that comes in goes to food or medicine," she said. Does yesterday's wage increase help the family? "No, in fact it makes the situation even more difficult. Every time wages go up, prices go up twice as much," Rosvelt replied.

"Almost all the teachers have left my university, I think 80% is gone," Axel says. "The oldest students have taken it up and are now teaching." Axel worries. "You can study, but who am I going to work for in Venezuela? There's no one to give me a job. If you're realistic, I have to say it's unrealistic to think that studying here in Venezuela is worth anything."

"Many young Venezuelans have left the country," he said. "My family also offered me to leave Venezuela, but I wanted to finish my studies, I would like to call myself a professional. But I also have ambitions. My dream would be to move to Canada, but that is not realistic, I would go anywhere possible at the moment."

"Yes, leaving Venezuela leaves the country without professionals, but we have to think of ourselves, of our family. The government gives us no choice but to leave. Personally, I am not protesting, several students have already died in demonstrations and death is not part of my future plans."

Later in the evening, over a beer from the cost of almost a day's wages, Joris and I talk about the day. It remains incomprehensible what has happened to one of the most oil-rich countries in the world. We wonder what tomorrow will bring, because every day in Venezuela seems to consist of unthinkable and unpredictable developments.

[This article was previously published on VICE.com under the title: Así se ve la Venezuela que no aguanta más la crisis]

By: Michel Baljet Photos: Joris van Gennip