America's military escalation in the Caribbean: the Venezuela crisis

The United States dramatically increased its military presence in the Caribbean this August and September, with Venezuela as its primary target.

As a Dutch journalist and investigator, my expertise lies in the dynamic fields of conflict and crisis areas. My scope of work has not only been limited to documenting the complexities of war situations, but has also included in-depth research on organized crime. Whenever possible, I have focused my efforts on improving the living conditions of children living in these harsh conditions. Over the decades, I have had the pleasure of working with a variety of news organizations, educational institutions and passionate individuals.

My path has led me through a broad spectrum of humanitarian challenges, always looking for ways to contribute to sustainable solutions and justice. With creative problem solving and a vast network, I have been able to tackle complex issues.

After a necessary stay in intensive care in August 2022, I am now on a recovery journey. While I cannot currently return to the intense working conditions I know, I am devoting myself to writing about recent events, sharing insightful pieces from my collection and starting new initiatives.

In doing so, I remain available for digital research tasks and providing solutions. Your support is invaluable to me now more than ever as an independent entrepreneur. It gives me the strength to continue my work and remain hopeful about making a lasting impact.

The United States dramatically increased its military presence in the Caribbean this August and September, with Venezuela as its primary target.

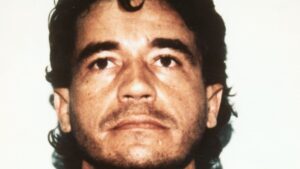

Carlos Lehder Rivas, a founder of the notorious Medellín cartel, has been released from custody in Colombia after a court ruling that his previous drug trafficking conviction

El Salvador, under President Nayib Bukele, has deployed a strict strategy against criminal gangs such as MS-13 and Barrio 18. This approach, known as the "Territorial

The assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021 has exacerbated Haiti's constitutional crisis. The parliament is no longer functioning and the judicial system is struggling with

On Jan. 3, 2026, U.S. fighter jets flew low over Caracas. Delta Force operators stormed a heavily secured compound. Forty people died. Nicolás Maduro and his wife