It is June 2024 and Haiti, the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere, once again faces a turning point. Faced with a crushing combination of political, humanitarian and security crises, the country once again appears to be teetering on the brink of collapse. As gang violence escalates, the question remains whether it will ever find peace again.

Gangs are increasingly occupying more of the power vacuum and are estimated to control around 80% of the infested country's capital. While the UN previously agreed to a Kenya-led multinational security mission in 2023, legal obstacles and financial difficulties have so far prevented it from coming to fruition. As a result, the power vacuum remains unabated, much to the chagrin of the population.

The assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021 has exacerbated Haiti's constitutional crisis. The parliament is no longer functioning and the judicial system is facing enormous problems. Late last month, the transitional council elected Garry Conille as the new prime minister; he arrived in Haiti this weekend. Will Conille be able to restore order and end the chaos gripping the country?

A nation in decline

Haiti's problems are not new. For decades, the country has struggled with poverty, corruption and instability. But in recent years, the challenges have reached critical levels. The assassination of President Moïse sparked a new wave of violence and anarchy. Gangs took control of large parts of the capital Port-au-Prince and surrounding areas. Rapes, kidnappings and murders became daily occurrences to spread fear among the population.

Historical background of gangs

The origins of armed groups in Haiti date back to the 1950s, when the dictatorship of François Duvalier created the paramilitary group Tonton Macoute to suppress dissidents. After the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, the Tonton Macoute was officially disbanded but never disarmed. Its members reorganized as vigilantes and continued to play a role in the country's political violence.

In 1994, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide disbanded the Haitian army and banned pro-Duvalier armed groups. This did not end the violence, however, as ex-soldiers and militias joined informal militant factions. During the 1990s and early 2000s, youth groups known as chimères emerged and were supported by the police and the government to consolidate Aristide's power. These groups took control of entire neighborhoods and became increasingly independent.

Evolution of gangs

After the devastating earthquake in 2010, youth groups became even more powerful. The earthquake led to mass escapes from prisons, strengthening the ranks of the gangs. Under the rule of President Michel Martelly (2011-2016), politicians accused of crimes were protected, further reinforcing the culture of lawlessness and violence.

By 2022, it is estimated that there were about 200 gangs operating in Haiti, half of them in the capital, Port-au-Prince. One of the most influential gangs is the "G9 alliance," led by former police officer Jimmy Chérizier, also known as Barbecue. This alliance controls large parts of the capital and has positioned itself as a revolutionary organization.

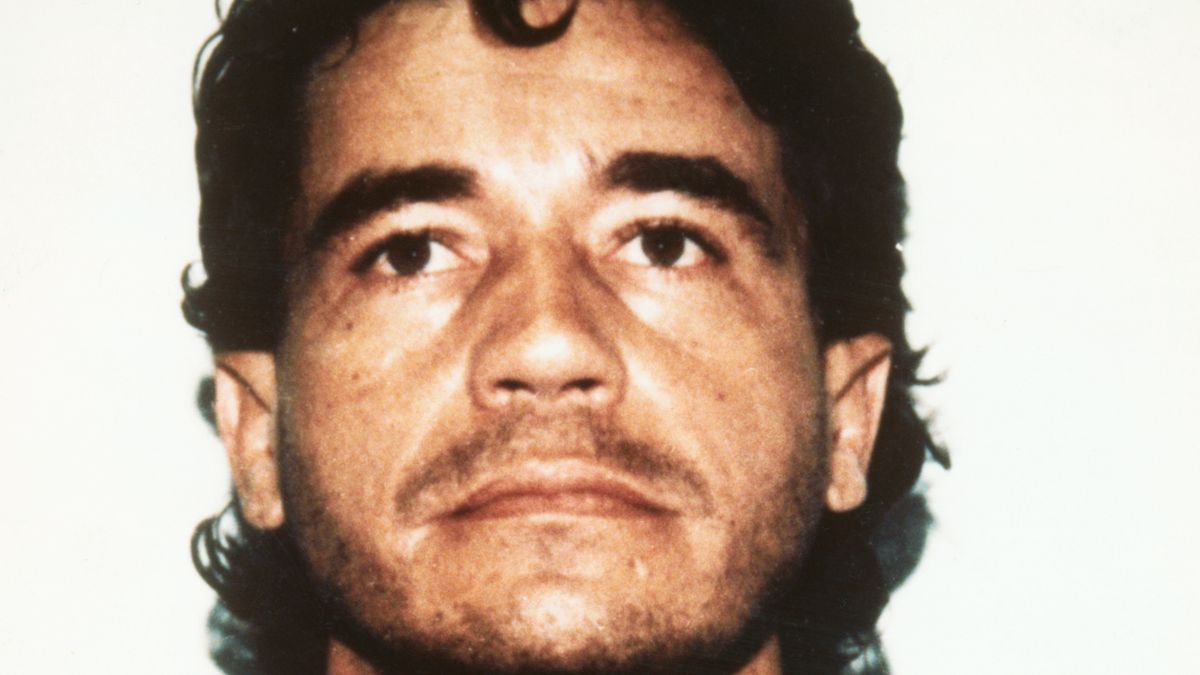

Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier

Jimmy Chérizier, better known by his nickname "Barbecue," is a former police officer who has become one of the most influential and feared gang leaders in Haiti. His life took a drastic turn when he decided to take the law into his own hands and join the world of gangs and organized crime.

As leader of the "G9 alliance," a coalition of nine gangs, Chérizier has acquired considerable power in the capital city of Port-au-Prince. His alliance controls large parts of the city, where it often calls the shots and provides both protection and fear to the local population. Chérizier justifies his actions by claiming he is fighting against the widespread corruption and inequality that plague Haiti. He positions himself and his alliance as a revolutionary organization that stands up for the rights of the poor and marginalized.

However, his claim to noble struggle is overshadowed by the numerous allegations of crimes against him, including murder. Despite these serious allegations, Chérizier remains a powerful and influential figure in the Haitian underworld and politics. As Haiti continues to struggle with gang violence and political instability, the role of Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier will undoubtedly remain a major topic of discussion and controversy. His story illustrates the complex and often violent realities of life in a country plagued by poverty, corruption and abuse of power.

The current situation

The current situation in Haiti is grave. Since late February 2024, the capital Port-au-Prince has been plunged into a state of violent anarchy. Gangs have reached not only the poorer neighborhoods but also the previously relatively safe and prosperous parts of the city. Residents of neighborhoods such as Pétionville, Laboule and Thomassin have fled the violence.

The gangs have attacked key infrastructure, such as electricity supplies, leaving parts of the city without power. Port-au-Prince's airport and port have been closed for a long time and are still not operating normally, leading to shortages of food and medical aid. The UN estimates that half of Haiti's population, about 11 million people, are currently starving.

As the Haitian people suffer from gang violence, political leaders struggle to find a solution. Prime Minister Ariel Henry, who took office after Moïse's assassination, failed to restore security. He resigned in March 2024 under the pressure and inability to control the chaos and violence in the country. In a video message, he said the country needs peace and stability.

A new hope

In these dark times, the appointment of Garry Conille as the new prime minister offers a glimmer of hope. Conille, a former UN official, has experience in Haiti. He was previously, from October 2011 to May 2012, prime minister of Haiti under then-President Michel Martelly and was former chief of staff to Bill Clinton in his role as UN special envoy to Haiti. Conille served as UNICEF regional director for Latin America and the Caribbean since January 2023. "Together we will work for a better future for all of our nation's children," Conille wrote on X as an initial response to his appointment. Conille was appointed as prime minister by Haiti's Transitional Council on May 29; he arrived in Haiti on June 1.

UN security mission

Part of the key to success will have to be international support. By October 2023, the UN Security Council had already approved the deployment of a Kenyan-led multinational security mission (MSS). But political and legal obstacles delayed implementation; for example, in January 2024, a Kenyan court ruled that it was unconstitutional to send Kenyan police officers to Haiti. This ruling is being challenged, but is still causing delays. In addition, the mission is facing financial problems, as the UN Trust Fund has received only $21 million of the required $600 million. Kenya was also keen to get paid in advance, but UN rules state that payment can only be made in arrears. Also, there are several operational challenges to the mission, including the heavy arming of Haitian gangs (and the lack thereof on the part of Kenyans), the risk of civilian casualties in urban fighting and possible corruption within the Haitian police. Despite these challenges, Kenya remains determined to lead the mission, with additional U.S. support.

A battle on multiple fronts

As Kenyan troops prepare for their mission, gang violence only increased last year in Haiti. The gangs, which by now had united and signed "Among themselves a non-aggression pact," launched coordinated attacks on government buildings and infrastructure. The Haitian police, understaffed and ill-equipped, could do little. It is estimated that today nearly 80% of the Haitian capital is in the hands of gangs.

Uncertain future

As Haiti enters the summer of 2024, the future remains uncertain. If and when Kenyan troops arrive and whether they will be able to deal with the gangs is still unclear. There are great uncertainties in breaking the cycle of violence and poverty. It will not be easy, and success is by no means guaranteed. The humanitarian situation also remains precarious, with high risk of disease and famine.

But for the first time since the taking of the power vacuum by gangs, there seems to be a possible way forward for this troubled country. The next few months will be crucial. Although many eyes of the world are not on Haiti, but mostly on Ukraine/Russia and Israel/Palestine, hope may be the only thing the Haitian people have left. Hope for a better future, hope for peace, hope for a new beginning for Haiti.