Looking out over the now empty, weed-covered site, it is hard to imagine that just over half a year ago nearly 10,000 people lived here. I went back to Calais to see what has changed since the evacuation of the Jungle, the illegal refugee camp next to the tunnel to England.

Standing on the hill, looking out over the former camp, I imagine what it was like at the end of October last year. The camp was burning in several places. Dark clouds of smoke filled the air. Several refugees packed up their last belongings, while the massed police swept the grounds.

While bulldozers are ready to raze their homes to the ground, the 8,500 refugees are driven like a herd of animals to a large chilly shed temporarily set up as a sorting center. They are then taken away in buses to be placed in various cities scattered across France. Saying goodbye to their dream "England.

Nothing of that camp is visible today -as if it did not exist. How will the former residents fare? We don't have to wait long for the answer. Less than three blocks away, in an open field between some industrial buildings, we find the first refugees. As if we had come to bring food, the first refugees come our way as soon as we get out of the car.

I did not travel to Calais alone today. One of the others who went with me is Bob Richters. It's his first time in this area. He didn't just go along to drop off a van full of donated goods. He wants to see for himself what is happening here.

Earlier in the day, we drove past a collection shed a few kilometers outside the former camp. Well-meaning volunteers collect donated food and goods here and then distribute them to the refugees. Tower-high items are stored. Skittishly, several volunteers watch our arrival; "keep the gate closed for security reasons. What are these cameras doing here. Don't film the location of the building, we have been attacked by extreme right-wing thugs in the past."

"I don't really know what to make of this," Bob tells me. "They offer no tools, nothing will be solved with this." I have to agree with him. Indeed, with all the good intentions, it offers no solution. I also saw the bad sides of this kind of charity last year.

Many volunteers take on tasks without being knowledgeable. Some take, consciously or unconsciously, an undesirable position of power and a deeper purpose other than sticking band-aids is lacking in many cases. Today there is food again, what there is tomorrow we will see.

One of the volunteers reports being greatly inconvenienced by the police. "We get an hour to hand out food at a location, then we have to stop" The organization Bob donated items to makes food for between 1,200 and 1,500 people daily.

Bob is his own little do-gooder. In Rotterdam, he helps the -in many people's eyes- underprivileged of our society with his project Hotspot Hutspot at three locations. Ex-addicts, homeless people and a girl indoctrinated by the IS are part of his clientele. "My project evolves as what is needed, for example, I now have two homeless people who are active with me, they need shelter, so I am now working on a hot spot hot spot hotel." "You know Michel, development assistance at home is what I do."

The field less than three blocks from the former "jungle" is dotted with people. In the middle of the field something like cricket is being played, next to me a little boy of a few years old is stepping along the piled up garbage, some others are asleep. One of the boys who walked up to us, a boy from Eritrea, I remember. He was one of the boys I met in the jungle in October. He was there for five months then, this means he has been in this area for a year now. He looks tired, his eyes are red. In his poor English, he tries again, as he did in October, to explain to me that he has a sister in Canada who is willing to take care of everything for him. "I don't need to go to England anymore," he asks me if I can mediate, again I give my number, a phone call I don't expect from her, still not.

The refugees in this field report sleeping in the open. A few say they are harassed by police, "They come at night, take away our belongings and spray pepper spray in our eyes." Some report being regularly picked up only to be released a few hours later. There are no facilities on the field, including water.

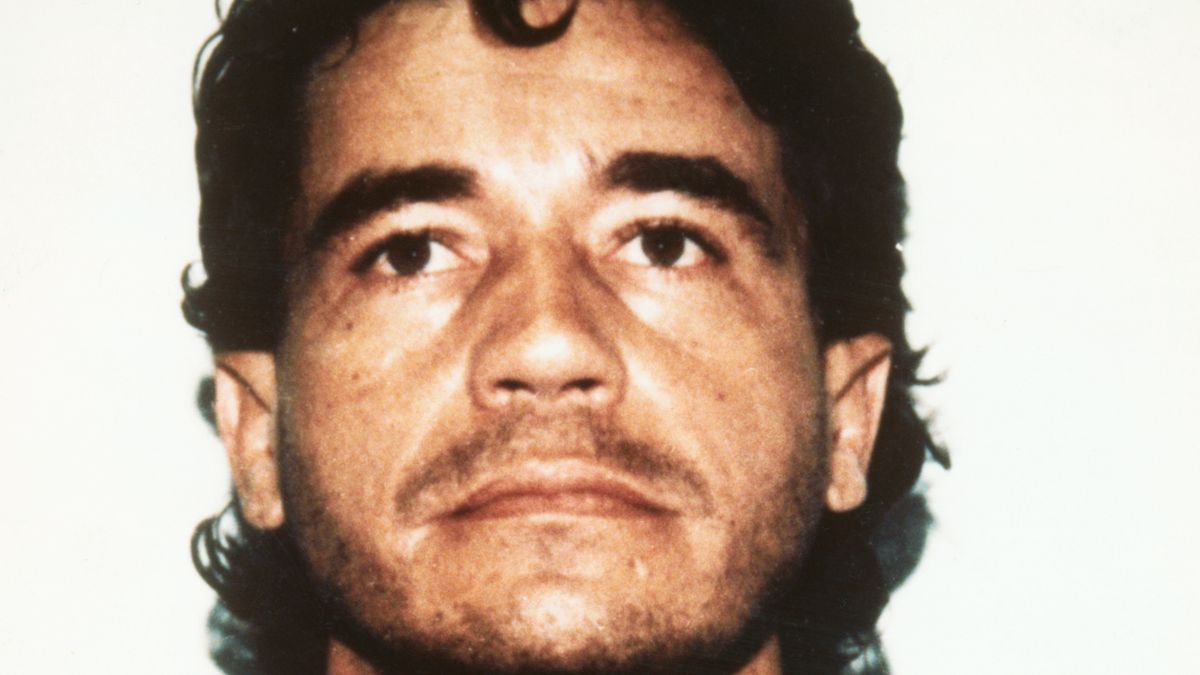

Last year I met Zimako, a Nigerian refugee who fled his country in 2011 after the elections. His Togolese father who had worked for the previous government was threatened. Via Libya and Italy, he ended up in France. Unlike others here, Zimako does not want to go to England. He wants to stay in Calais.

Zimako has grown fat when I meet him today, he is here because he is meeting with Bob and with Veerle. They have brought a washing machine, a dryer and monitors for him.

Until the eviction, Zimako had a school in the refugee camp the jungle. His -handily built- school was razed to the ground along with the rest of the jungle. Even before the eviction began, Zimako had a new project, a laundromat for the refugees and residents of Calais. Now he also wants to start an Internet cafe.

I don't know what it is but unlike last year, I miss the confidence with him when he talks. The washer, dryer and monitors end up in a basement of an apartment complex and the story he spins in front of my camera seems too scripted, including his jokes. Is Zimako still the do-gooder and ray of hope in the gates of hell I wrote about last year? Was it just me, have I become too suspicious because of the refugee hatred in the Netherlands?

As I stand on the edge of the field, staring at what is taking place before me and watching my half pack of shag being distributed to a dozen or so refugees, Bob comes over to me. "And Michel? How do we solve this, do you know the solution?" I don't think I give him an answer to that question. And as we drive past -the police cars parked just around the corner- I hear Bob say to two of his boys who are along for the ride "Tailor-made, talk to them one by one and come to a solution."

Personally, I think Calais is a great example of how we, in Europe and also in the Netherlands, deal with refugees. We don't solve the problem, we move it and pretend that everything is cake and egg. We continue to make the same mistakes we made in the past. We segregate, create a new class and get distracted by discussions of whether we as human beings have any responsibility at all for another human being. Only to find out ten or twenty years from now that these new Dutch people are going to turn against the established order.

And as we do so, not only are the thousands of refugees in Calais sleeping in the open, waiting for the day that may never come.