While Venezuela is on hiatus, in prison life goes on as usual. Journalist Michel Baljet and photographer Joris van Gennip are met at the entrance by two armed prisoners, meant to keep guards out. Welcome to Tocoron, one of Venezuela's most notorious prisons.

Next to me walks a young soldier with an oversized machine gun around his shoulder. Joris, the photographer who traveled with me to Venezuela, walks behind me on the right, our fixer on the left. We have been walking for a few hundred meters along an unpaved dirt road, which we feel leads nowhere, when I again ask Joris to be extra vigilant. From the other side comes a motorcycle with two more soldiers.

Forbidden area

Over an hour earlier, Joris and I arrived at Tocoron to do a report on life in one of Venezuela's most notorious prisons. What was supposed to be a routine job did not go as planned. While we thought we had bribed all the soldiers guarding the outside gate of the prison, our belongings - some cameras and other equipment - were taken away by a major. After mutual consultation, he sent us and the young soldier up the deserted road that ran alongside the prison.

The motorcycle carrying the two soldiers comes to a stop and the soldier accompanying us talks to his colleagues. After a few skittish glances our way, it is decided that we should turn around, to walk back to the prison gate. It will never become clear why we had been sent in this direction in the first place.

After that, things moved quickly. At the gate, we didn't get our stuff back, but were allowed to walk through. In my pocket was another phone that we could use to take pictures. We decided to go in without equipment anyway. Walking into the prison, we breathed a sigh of relief, both with the feeling that this might have ended very differently. From here we encountered no guards, no military and no government employees. Indeed, from here on out, it is off-limits to them.

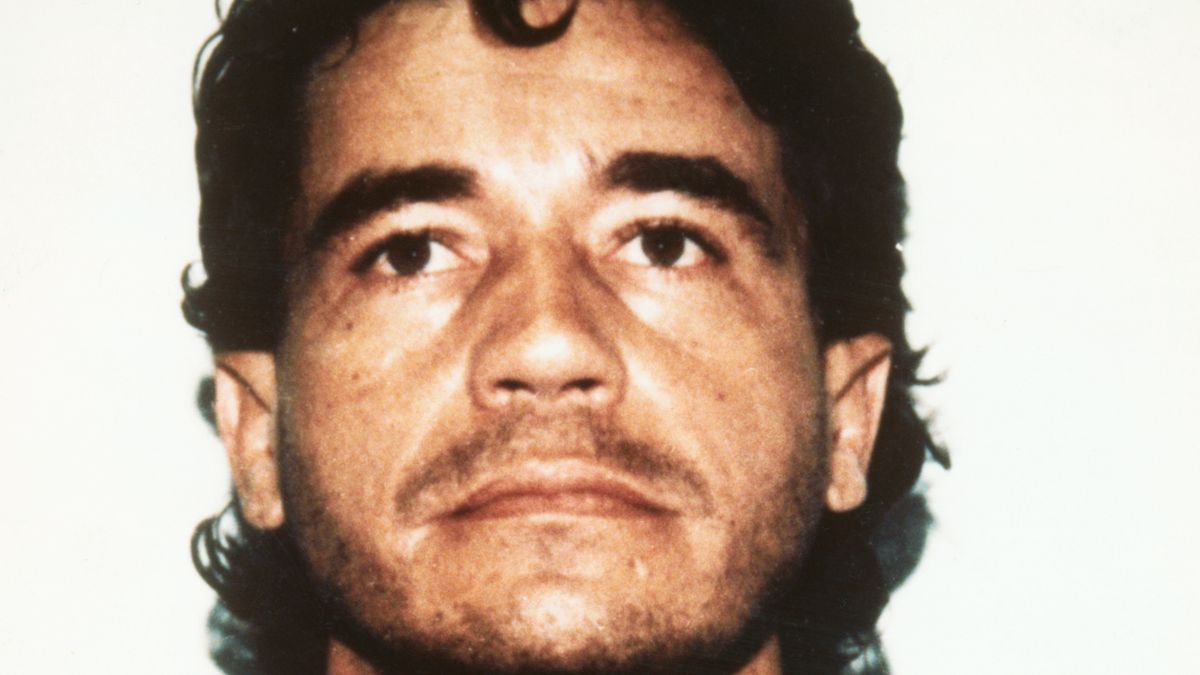

We walk into the world of Niño Guerrero, an inmate who has been running this prison along with his accomplices for years. The authorities gave up controlling the prison years ago and now focus only on guarding the prison's fence. In 2012, Guerrero escaped with several accomplices, a year later he was back and since then he has not stopped for a day to build his empire. Héctor Guerrero Flores, aka Niño Guerrero (The Warrior Child), is a ruthless leader with two faces. Where on the one hand he keeps the prison and his criminal empire running with an iron fist, on the other he is known as a benefactor. Like a modern-day Robin Hood, he lifts families out of poverty and distributes wheelchairs and medicine to those in need. The Warrior Child not only runs the Tocoron prison; his former neighborhood of 28,000 is also completely under the authority of him and his men. If our fixer is to be believed, his power goes much further.

Power grab

Tocoron, built in 1982 for 750 prisoners, today houses more than 7,500. For years, the government has had no say here. In fact, at the entrance leading to the center of the facility, two armed inmates stand to keep guards out. 3 years ago this security was even more extreme, when there were prisoners with machine guns and you could find an armed prisoner on every street corner. Recently, Niño decided to replace these weapons with knives on visiting days. 'For imaging,' I later learn.

Most of the bullet holes are from a conflict that took place a few years ago. In a firefight that lasted hours, Niño won back his power

This is not the first time Joris and I have been here. Last week we were there as well. Both fascinated by the developments inside this prison, we decided to go back today. The first time I visited this wonderful world was in 2014. I even volunteered there for a few days to understand what is going on here.

Walking through the gate of the prison, you come to a main road leading to the center of the prison. To its left are the two buildings that once formed the original prison. Inmates are doing restoration work on the flat; they are about halfway there. Under the newly applied exterior coating, bullet holes are still clearly visible. Most of these bullet holes are from a conflict that took place a few years ago. A prisoner was of the opinion that not one person should be in charge within the walls of Tocoron. Niño disagreed. In a firefight that lasted for hours, Niño won back his power. Dozens of people did not survive the power grab. The official death toll stands at 16. Videos taken by prisoners, however, show us a much higher death toll.

Subordinate

Right after the entrance, we find a square on the main street with a basketball court. A stage is ready and the boxes for a performance later in the day are set up. Next to the plaza is the newly renovated swimming pool with a playground for the youngest visitors.

Walking down the main street for a while, we come to the center of the prison. While there is a major food crisis in Venezuela right now, it does not seem to exist here. Several stores and restaurants offer all kinds of food and necessities. Here, unlike in the outside world, customers do not have to stand in line for hours before making a purchase.

Nor is a swimming pool lacking at Tocoron Prison, which is doing better economically than outside its gates.

While developments in Venezuela have stalled in recent years due to a shortage of building materials, developments in Tocoron have continued apace. For example, several buildings that were plywood when I visited 3 years ago are now concrete.

The small, autonomous city offers numerous amenities for those who can afford them. For example, you can get a television connection for 100,000 bolivar a week (a monthly wage). Residents of Tocoron pay an allowance to stay in prison; if you can't pay that, you become a subordinate, recognizable by a tie. You must then work for Niño to pay for your place inside the prison. Subordinates are allowed to walk around and stay in a locked part of the prison only with permission. Subordinates help visitors lift luggage, do maintenance work and drag large buckets of water through the prison. Every day they receive a government-paid meal. We see a long line of skinny men waiting in the afternoon as food is distributed from large pots.

Banco de Tokyo

Tocoron is structured in sectors. The closer you are to the center, the better the amenities. So you have cabins with or without air conditioning, and with or without TV. If you do very well, you can have a store on the main street, with an adjoining bedroom.

There is a bank: the Banco de Tokyo. Prisoners who want to transfer money can have it done to one of the many accounts of Niño's henchmen. After deducting a 10 percent commission, you can collect your money. Borrowing money is also possible, at interest rates between 10 and 20 percent. But oh woe if you pay back late.

Joris and I had decided that it was not smart to walk into prison with large piles of money. Due to the massive inflation in Venezuela, 100 dollars is worth 430,000 bolivars today (now even 600,000). Recently there have been new banknotes up to and including a value of 20,000 bolivar; however, these are nowhere to be had. The largest bill available has a value of 100 bolivar. Instead of putting over 4,000 bills in a backpack, we decided to bring dollars. As we had been told, we had these exchanged in no time at a good rate within the walls of Tocoron.

Together with our fixers, we do a tour of the prison. One of the fixers has been stuck here and knows many people inside the walls. With every turn we make, I see photographer Joris' amazement increase. Besides the pool, playground equipment and shopping, Tocoron has plenty of other amenities. For example, there are bars and Tocoron has the most famous disco in the region: Disco Tokyo. Famous artists from home and abroad perform there, and there is even airtime purchased on the radio to announce the next party. Currently, the disco is being renovated; from what I understand, the just-new marble floor is being replaced with a lighted floor.

Corrupt arms deal

A little further on we walk into the zoo. While the inhabitants of the zoo in capital Caracas are starving, here we see the opposite. A wide assortment of animals, including flamingos, monkeys and a panther live in a well-maintained area on the north side of the prison. Food is plentiful, day and night inmates keep busy caring for the animals. A new arena has been built in the zoo for cockfighting, and further along is a stable with competition horses.

Cockfights also regularly break out in Tocoron.

Through the pigsties, we walk past the baseball field to one of the prison's quarters. It is a coming and going of motorcycles, a mode of transportation available only to Niño Guerrero's henchmen. Small houses made of plywood form a kind of slum here. This is still the better part of the prison. Entering one of the houses, we enter a small room with a double bed. White A4s make up the wallpaper, the roof is neatly sealed with a system ceiling. It is cool, the air conditioning is on, a music program is on television.

With the weapons and grenades at hand, Niño and his crew can win a small war

Back downtown, Joris and I, over a beer, talk about what we've seen. "I actually feel safer inside the prison walls than outside," Joris says. Indeed, at first glance, it seems that the gigantic crisis currently plaguing Venezuela is passing Tocoron by. Developments continue apace. Food is plentiful and everything functions. You would almost forget that you are not in a resort, but in one of the country's most notorious prisons. Hundreds of people die there every year. In fact, a day after our visit, three bodies are found at the gate of the prison. And a week later another one.

Empire

To maintain order, Niño Guerrero's henchmen are armed with modern, sometimes automatic weapons. In a corrupt arms deal with the government in 2014, more than 1,400 weapons were turned in. For that, at least as many more modern ones were returned through the back door. With the weapons and grenades on hand, Niño and his crew can win a small war. In addition, Niño has a court in his prison, of which he is the judge. While Venezuela does not have the death penalty, in the court of The Warrior Child, that is different. We are shown gruesome pictures of lifeless people from various prisoners, some mutilated before they were murdered.

Niño and his men live a safe distance away at the edge of the prison. His home appears to be fully equipped and is guarded 24/7. Niño's revenue comes not only from cell rental fees, but also from a commission on restaurant and bar sales, gambling revenue, his bank, extortion, drug trafficking and theft. According to officials, 90 percent of crime in the region has a link to the prison. It even goes so far that a carjacking victim will get a call from Tocoron a few hours after his car is stolen with the amount of the ransom to get the car back. The victim may then come and pay this off inside the gates of the prison, after which he or she will get back the location of the car as well as the key. The price to get your stolen car back is between one and seven monthly wages, depending on how new it is.

It is difficult to estimate how much Niño Geurerro's empire is worth. A rough calculation tells us that at the current rate he is bringing in around 200 million bolivars with the rent payments alone, or nearly 2,000 regular monthly wages. The rent payments are just the tip of the iceberg.

Greetings from The Warrior Child

After talking to some people and walking around a bit, we decide it's a good time to go. On going out, the major who took our belongings does not want to give them back. A plea from our fixer does not help. Even offering money, something that is the order of the day in Venezuela, offers no relief.

A prison with a zoo, anything is possible in Tocoron.

To still try to get our cameras and other belongings back, we try to get in touch with the Guardia National outside the gate. A phone call to inmates inside Tocoron offers relief after a few hours. In the evening, when we are back in Maracay, the redeeming call comes: 'Your stuff is no longer with the major but in the prison.' The next morning we can come and pick it up.

Early the next morning, we drive back to Tocoron. And lo and behold, after an hour of waiting, an accomplice of Niño Guerrero walks out of the gate of the prison with our shoulder bag. Everything is still in it. What that cost us? Nothing, courtesy of The Warrior Child.

PHOTOGRAPHY JORIS VAN GENNIP AND MICHEL BALJET