As soon as I walk through the gate of her home in Cabimas, I get a hug that doesn't seem to stop. These have been difficult days for her. Last week, she received her first cancer treatment. She was lucky; the drugs needed for treatment were crowdfunded by her daughter who lives in Europe. The cost for 10 treatments? Converted to 820 monthly wages. A week earlier, one of my team members brought the drugs from Caracas to Cabimas, 700 km away.

Lying in her hammock, she recounts the events of the past few weeks, how she dropped a few eggs earlier today and could well cry, and especially how she was shocked afterwards that she has to cry over something as simple as broken eggs - due to hyperinflation, a box of eggs now costs one month's salary.

My cousin is dying

Something extraordinary happened. I posted on facebook a picture of the bizarrely high bill for her medication, 2.1 billion. Another facebook friend responded. Lilia: 'My cousin is dying, no medicine, a tumor in his head'. I contact Lilia a learn that her cousin Julian (24) is in a public hospital in Caracas. We decide to look for him.

Julian's grandmother lives in a suburb of Caracas. With tears in her eyes, she recounts Julian's childhood. 'He was a serious boy, didn't smoke, rarely drank,' even after the diagnosis, he remained strong, no one understands where he got his zest for life and energy all this time.

Several years ago, his health deteriorated. At first the family had money to have him admitted to a private clinic, but as the country's inflation was rapidly increasing, the money ran out "all the money went to medicine and food." On top of that, the family lost money as it ended up in the pocket of a specialist, who ended up disappearing abroad with the money without providing treatment.

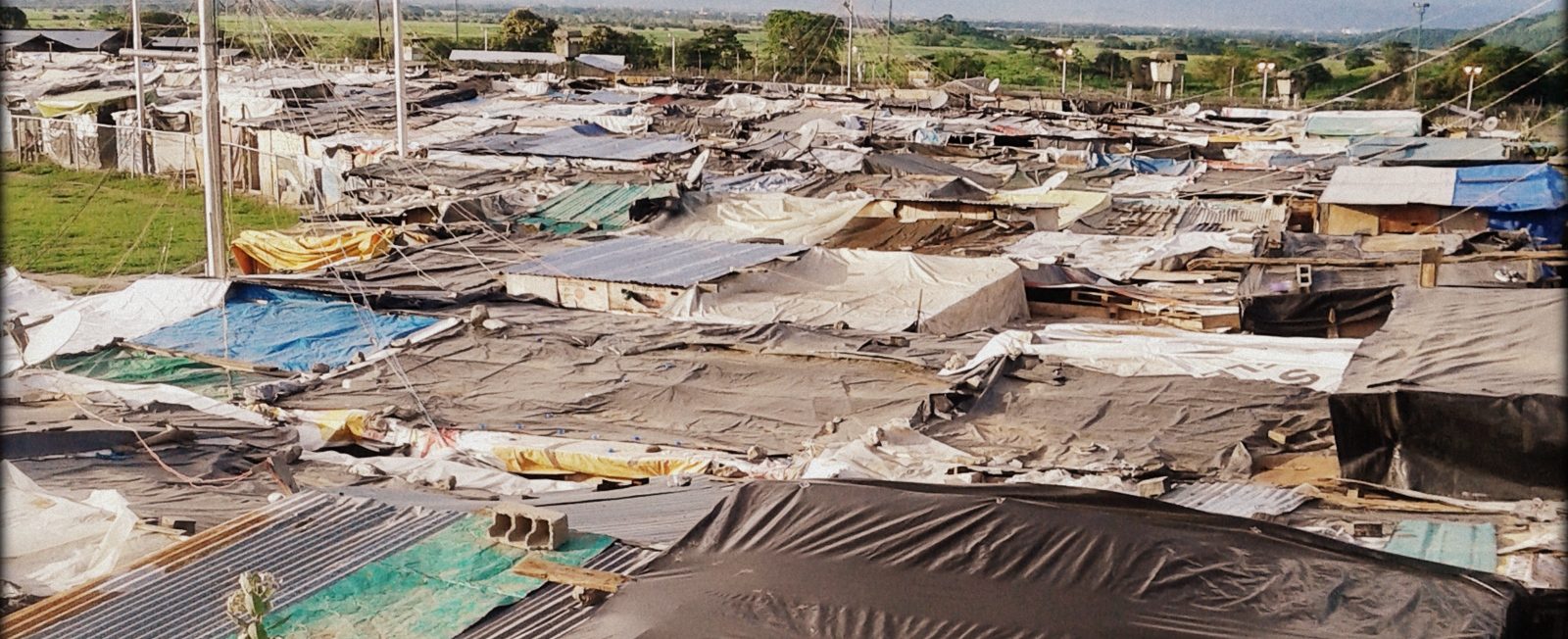

Julian ends up in El Llanito, one of the largest state hospitals in Caracas. The family goes to the government to apply for support, eventually it would take two years to actually receive the first support.

Medications are resold

The medical world in Venezuela is going through a huge crisis. Medicines are almost impossible to get and imported medicines are unaffordable. Cancer, AIDS and dialysis treatments have been stopped. Many hospitals have closed or are nearly non-functioning; many doctors have fled. A few weeks earlier, I stood in front of a Barquisimeto hospital talking to a group of medical students; none of them planned to stay in Venezuela after completing their studies. With a monthly salary of less than 12 euros converted, the doctors who have remained can hardly make ends meet themselves. Medications meant for patients are not administered but resold privately, with hand money you get priority and better treatment.

Pilot, teacher or chef after all

As a child, Julian wanted to be anything and everything. Pilot one day, teacher the next, Julian's mother let me know in one of our conversations. A treasure, he learned hard. Before he got sick, there was a moment when he decided to become a chef and sold shoarma at the garage of his house. Unfortunately, his hands were not fast enough (anymore), but he tried anyway. On weekends, he spent a lot of time with his grandmother and grandfather. The latter was like a father to him. In general, he was a good boy. Except for normal things like cleaning up the laundry, he never made trouble or argued. His life consisted mostly of studying, eating and sleeping. And even now during his illness he talks about continuing his studies at university and starting his own business.

Monitored by government agencies

Julian's grandmother invites me to visit the hospital. 'They don't have anything in the hospital. I have to bring everything food, medicine, cleaning products, they don't even have water there,' the grandmother informs me on the way. The Llanito hospital is guarded by government agencies; at the entrance to the hospital is a checkpoint of the Guardia Nacional, and members of the Guardia also walk through the hospital. Outsiders and certainly journalists are not welcome here, but the grandmother manages to sneak me past the checkpoints.

Deplorable conditions

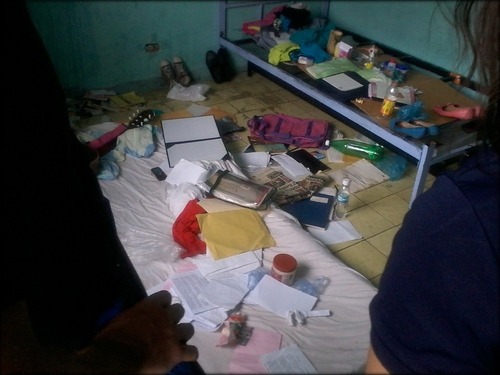

Most of the lights are not working, but one of the four elevators in the hospital (not maintained for years) is functioning. It's filthy, it stinks. I am carrying the bag of food when we walk into Julian's room; it turns out he is not there, but is in the intensive care unit. We seek him out, something that will prove more difficult than previously thought, as we are initially denied access. Only later would I notice how wretched the conditions of intensive care where, due to lack of cleaning and disinfectants, your death sentence is almost certainly signed. 'I visit him every day, if I can't take the car or the subway I'll walk,' the grandmother tells me as we walk away from the ward. A nurse calls after us 'don't forget to buy soap and diapers'.

Downhill

After a long diagnosis, Julian is told that he has a brain tumor that is not treatable (ed: in Venezuela), from there it goes downhill. Necessary antibiotics cannot be found, for other medications the family also has to search by themselves, and even the catheter and IV bags are no longer in stock at the hospital.

Julian's situation worsens, he can now communicate only with his eyes and is incontinent. He contracts meningitis. According to Julian's Mother, he contracted it in the hospital. At home, they have taken precautions, such as keeping sick people away from Julian.

A few days after my visit with Julian, a nurse comes to tell the mother that she needs to visit her son because it is believed that he will not make it through the morning. She sees that Julian is no longer "with it" by then and that he can no longer breathe on his own, "he no longer responded to touch." I then asked God to deliver Julian from this suffering. 5 Minutes later, mother is called back and learns that her son has fallen into a coma, 5 minutes later Julian dies at the age of 24.

Burial costs 60 monthly wages

Julian's family is lucky, the funeral can be paid for because Julian's grandfather used to work at a university. They contributed, and the mother's employer also contributed 20 million. The total cost of the funeral was 300 million (ed: converted 60 monthly salaries plus bonuses). The coffin had to be rented. The mother let me know she was lucky to have a large family to help, "family members did everything they could. Cousins, for example, helped look for medicine on the Internet'. Others do not have this and are on their own.

Sometimes the family could not stay at the mortuary because of the smell of corpses. There are too many dead and "some people don't have money for the funeral and leave the body there.

For his funeral, mother bought white roses to hand out to loved ones. One of the people who received such a rose told that Julian had once given her one of those as well. 'When he was little he brought it to my work. Everyone loved him. He was very innocent, different from others. I cannot accept that a person of his character should die this way'.

Government's fault.

Mother feels Julian's death is the government's fault, she worked as a teacher for 15 years and insurance has not helped her now. "It's the government's fault.". "Maduro should send people to see what is happening in the hospitals. I can't understand that he doesn't know, if he sends people he can see the suffering and need of the people."

In contrast, the government kept the rate of the Dollar artificially low for decades. 1 Dollar was 10 bolivars, but only obtainable by companies that were friends of the government. Since 85% of products are imported into Venezuela -and there was almost no production in its own country- the government managed to keep power over the food trade this way. In recent years, the government did move somewhat away from the one rate policy. Now they operate several. All still far from the black market rate.

In contrast, the government kept the rate of the Dollar artificially low for decades. 1 Dollar was 10 bolivars, but only obtainable by companies that were friends of the government. Since 85% of products are imported into Venezuela -and there was almost no production in its own country- the government managed to keep power over the food trade this way. In recent years, the government did move somewhat away from the one rate policy. Now they operate several. All still far from the black market rate. Meanwhile, the minimum wage is falling rapidly. With today's average black market rate less than $2 a month. People are selling their possessions, getting into crime or whoring themselves out. Corruption was on the rise. Hundreds of thousands of people fled the country in recent months.

Meanwhile, the minimum wage is falling rapidly. With today's average black market rate less than $2 a month. People are selling their possessions, getting into crime or whoring themselves out. Corruption was on the rise. Hundreds of thousands of people fled the country in recent months.