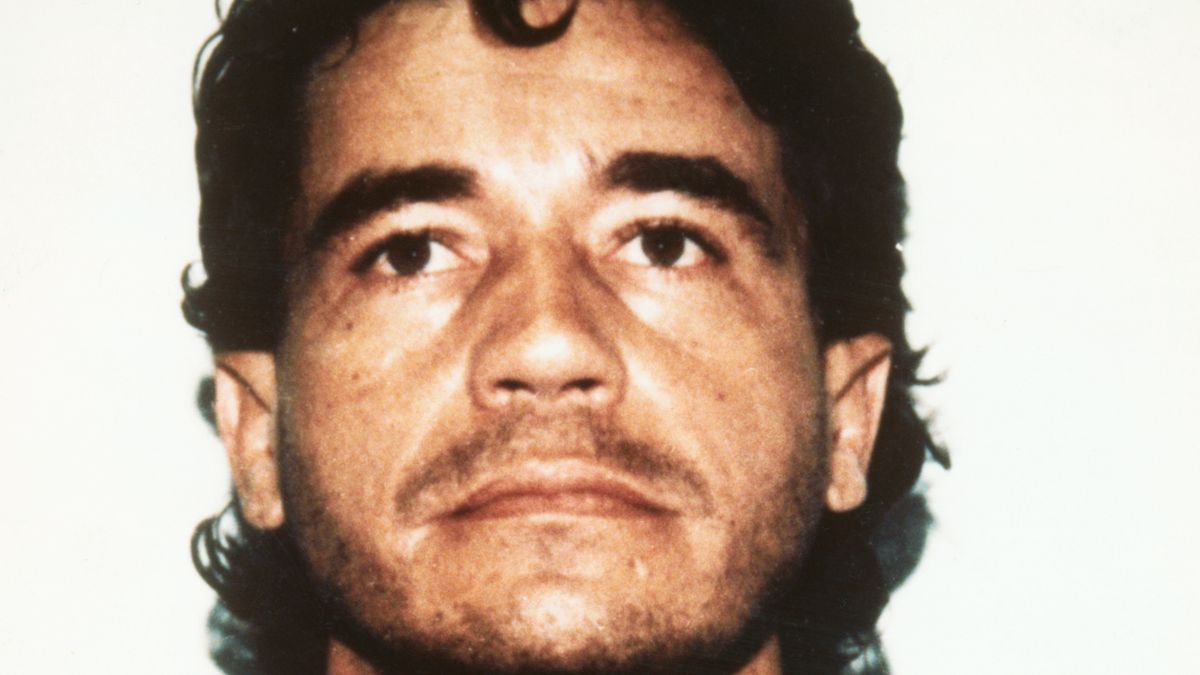

On Jan. 3, 2026, U.S. fighter jets flew low over Caracas. Delta Force operators stormed a heavily secured compound. Forty people died. Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores were taken away in handcuffs to a New York prison. It was the United States' most spectacular military intervention in Latin America in decades. Donald Trump declared that America would "run" Venezuela until a secure transition was completed.

Four weeks later, Maduro is behind bars, but his regime still stands. His former vice president Delcy Rodríguez is now implementing the same policies, backed by the same security forces, the same paramilitaries, and the same repressive apparatus that held Venezuela in its grip for more than a decade. Venezuelan opposition leader María Corina Machado - Nobel laureate, symbol of democratic resistance, the one who would have won the 2024 elections - is sidelined. Trump called her "not fit" to lead. She does not have the respect, he said, nor the support within the country.

This is not transition. This is consolidation. America has removed the head of the regime but left the body intact, and now it speaks through that mouth.

The paradox of Trump's choice

The logic behind Trump's decision is easy to understand but hard to defend. Stability over democracy. Transaction over transformation. The White House chooses continuity because the alternative - a real change of power - carries risks that Washington is unwilling to bear. A completely new government under Machado could destabilize the Venezuelan security apparatus. Generals could mutiny. Paramilitary groups could lose control. The country could implode. America would be held accountable.

So Trump opts for what Ryan Berg and Alexander Gray call "managed authoritarianism": a manageable authoritarianism in which America sets the direction without taking day-to-day responsibility for the country. It's a logic familiar from decades of American foreign policy in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Central America. Put a leader in power who serves your interests, regardless of whether that leader is democratically legitimized.

The problem is that this approach perpetuates in Venezuela the same structures that have driven the country to the abyss. Delcy Rodríguez was not just Maduro's vice president. She was architect of his repressive system. She supported electoral fraud, violent suppression of protests, and systematic human rights violations. A UN report from 2025 documents how intimidation, arbitrary detention, torture and disappearances were carried out as state policy under her watch. This is the apparatus Trump now relies on to maintain order.

The US is using three push buttons to control Venezuela: access to oil, lifting of sanctions, and legal prosecution of individual leaders. Marco Rubio - who does show sympathy for Machado - emphasizes that America wants to see drug penalties stop, Iranians, Cubans and Hezbollah removed, and the country return to "normality." But what is normality in a country where the justice system does not work, where elections are not free, and where the economy is entirely dependent on a shadow network of sanctions-avoiding oil ships?

Machado: betrayed but not defeated

María Corina Machado is a political anomaly. She won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2025 for her fight for democracy. She presented the medal to Trump in recognition of his pressure on the Maduro regime. She called him a "visionary." She said his military intervention would mean for the Americas what the fall of the Berlin Wall meant for Europe.

Days later, Trump set her aside.

Her position illustrates the tragic irony of Venezuela's situation. Machado is the country's most popular politician. Her candidate, Edmundo González Urrutia, in all likelihood won the 2024 elections by a landslide, but the regime refused to publish the vote count and declared Maduro the winner. The opposition systematically collected evidence of electoral fraud. The international community recognized González as the legitimate winner. Maduro remained in power.

With Maduro gone, one would expect democratically elected leaders to come to power. Instead, Delcy Rodríguez rules with American approval. Machado is in Washington, holding talks with Trump, giving interviews to Fox News, saying she wants to return to Venezuela as soon as possible. But returning means possible arrest. The security apparatus that served Maduro now serves Rodríguez, and has no reason to trust Machado. She has spent 20 years accusing regime officials of human rights violations. Why would they give her power now?

Trump said recently that he "may be able to engage her in some way." That is not a commitment. That is a vague promise to someone he sees as a potential ally, but not a leader. Machado's own response is telling: "I will be president when the time comes. But it doesn't matter. That has to be decided in elections by the Venezuelan people." She knows her moment may never come.

What Venezuela really needs

If you are serious about solving Venezuela's crisis, you have to start by acknowledging what has gone wrong. Venezuela is not poor because it has no resources. The country has the world's largest proven oil reserves - 300 billion barrels, some 17% of the global total. In 2008, Venezuela produced 2.3 million barrels a day. By 2025, that had dropped to 700,000 barrels per day, a drop of 70%. Hyperinflation, famine, the exodus of eight million Venezuelans - all this is the direct result of systematic theft, mismanagement, and an economic system that used oil revenues not for the Venezuelan people, but for personal enrichment and political control.

America's sanctions exacerbated this process. Between 2017 and 2025, U.S. sanctions prevented Venezuela from accessing international financial markets, selling oil to Western buyers, and importing parts to maintain its production. These sanctions were intended to put pressure on Maduro, but they mostly affected ordinary Venezuelans. The economic collapse drove millions out of the country, creating the migrant crisis that Trump now fears so much.

What Venezuela needs now is not a new regime making the same mistakes. What the country needs is:

First, real democratic elections under international supervision. Not in two years, not after a "transition period," but as soon as is responsible. Machado and González have a mandate from the people. That mandate must be respected or reaffirmed in free elections.

Second, dismantle the repressive state apparatus. The paramilitary colectivos, the political police SEBIN, and the corrupt military top must be dismantled. This cannot be done by leaving these same structures in place and hoping they will behave differently under a new leader.

Third, restoration of the rule of law. Venezuela's judicial system was completely politicized. Judges who ruled independently were dismissed. The Supreme Court functions as an instrument of executive power. Without an independent judiciary, there is no guarantee of human rights, property rights, or fair trials.

Fourth, economic reconstruction that does not revolve exclusively around oil extraction for U.S. companies. Trump has already said that U.S. oil companies will fix Venezuela's "broken infrastructure" and "make money for the country." But if that oil revenue is not managed transparently and does not benefit the people, Venezuela will repeat its history. China already has contracts for fields. American companies like ConocoPhillips have claims to explored property. If Washington controls those oil revenues directly, there will be little fiscal space left for domestic reconstruction.

Fifth, regional cooperation without hegemonic control. Venezuela's neighbors - Colombia, Brazil, Guyana - all have an interest in stability. But that stability cannot be enforced by military threat or economic coercion. A regional approach that takes Latin American relations into account is essential.

The solutions out there

The reality is that there are no quick fixes. Venezuela's problems are built up over two decades. The country's collapse is the result of structural mismanagement, systematic corruption, and a political system that criminalized dissidence. You don't solve that by removing the head of the regime and leaving the rest intact.

However, there are conceivable scenarios in which progress is possible:

A gradual transition in which Delcy Rodríguez recognizes that her position is untenable and elections are held within six months. This requires pressure from both America and regional actors such as Colombia and Brazil. It also requires guarantees for regime officials that they will not face mass persecution - a difficult pill for victims of repression, but potentially necessary for peaceful transition of power.

A truth commission on the South African model, documenting human rights violations without automatic prosecution. This creates space for reconciliation without guaranteeing impunity. The International Criminal Court remains as a backstop for the most serious crimes.

Economic aid that does not come exclusively from Washington. Europe, Canada, and Latin American countries can contribute to reconstruction without the political conditions that often accompany U.S. aid. This also reduces China's influence without making Venezuela completely dependent on the US.

A new constitution that introduces checks and balances. Venezuela's current constitution - drafted under Chávez in 1999 - concentrates power with the president. A new constitutional framework with independent institutions, term limits, and federal structures could prevent a repeat.

The likely reality

But let's be realistic. None of this is on Trump's agenda. His focus is on three things: oil, drugs, and shutting out Chinese influence. Democracy is a byproduct, not a goal. Marco Rubio speaks fine words about freedom and human rights, but the reality is that Washington works with Delcy Rodríguez because she controls the military and paramilitary structures that can guarantee stability.

The danger of this approach is that it keeps Venezuela in a permanent state of "managed authoritarianism" - enough stability to limit migration and keep oil flowing, but not enough freedom to develop real democracy. It is a balance that works in the short term but is unsustainable in the long term. The underlying tensions - economic inequality, political exclusion, social fragmentation - remain. And when America loses focus, what happens?

We have already seen this story. In Iraq, George W. Bush declared "Mission Accomplished" in May 2003. What followed were years of insurgency, civil war, and instability. In Afghanistan, the United States withdrew, leaving behind a government that collapsed within months. In Libya, regime change led to a fragmented torn state with no functioning central authority. Venezuela risks the same trajectory: a tactically successful operation that fails strategically because the fundamental issues are not addressed.

María Corina Machado continues to talk about returning. She says she is needed in Venezuela. She is probably right. But Trump has made it clear that he does not see her as a leader. He opts for what he knows: deals with strong men, transactional relationships, and economic extraction. It is a pattern repeated throughout the history of U.S. interventions in Latin America.

The question is not whether Venezuela can change. It can. The question is whether America will let Venezuela change. Right now, the answer seems to be no. And that is tragic, because the Venezuelan people have already suffered enough from leaders who subordinate their interests to external power. Whether that power comes from Havana, from Moscow, from Beijing, or from Washington - for ordinary Venezuelans it makes little difference if they have no voice in their own future.