In recent days, there has been a lot of buzz around my decision to bring remains of MH17 back to the Netherlands. This is my side of the story.

On Sunday, December 25, I left (along with Stefan Beck) for Donetsk via Warsaw, Moscow and Rostov. The purpose of the trip was (among other things) to research DNR daily life and developments in eastern Ukraine since the war began in 2014. Many stories are going around about what is going on there, and many of them contradict each other. In total, we spent two months preparing and taking into account all possible scenarios including those related to security.

Why via Russia.

It was ultimately chosen to travel to the DNR via Russia. Another, more logical in some people's eyes, route would have been to do so via Ukraine. There has been a war going on in eastern Ukraine since 2014. There is no country that currently recognizes DNR. My goal of the trip was not just to find out what is happening on the front lines, but rather to see what the daily life of the residents is like and the internal political developments within DNR. Apart from the fact that it is almost impossible to travel to that area via Ukraine at the moment, and also to get press permits, it was not a logical choice for us to enter the DNR area from (in their eyes) hostile territory to expect cooperation afterwards. After consultation with the Russian Consulate, among others, and contacts within the DNR, the Russia route was chosen.

Visiting the MH17 crash site.

Given we only had a limited number of days, visiting the site where MH17 crashed two and a half years ago was not on the shortlist of things I would do. The conversations I had in the first few days with various people from the area decided me to adjust the schedule and visit the crash site for a day after all. Stefan Beck did not go with me that day. Arriving in the area I found to my surprise in several places still clearly recognizable debris. After some longer consideration, I decided to take a selection of debris with me. Most of it was aluminum and plastic parts and circuit board. I wanted to take these things with the goal of having them researched, to turn them over to the authorities, and to make a strong point that after 2.5 years things can still be found. Among the parts I found fragments that strongly reminded me of bone remains. Earlier bone remains were found, some turned out to be not human but animal. I am not a forensic examiner but did not rule out that they could have been bone remains of a human being. I made the consideration to take one of the bone remains for further investigation in the Netherlands. The consideration for me was: if these are human remains then they do not belong here but should be returned to the Netherlands.

Taking stuff with you.

The MH17 crash site is about 3 hours travel from Donetsk. An area where there are a few houses and a sort of simple first necessity store. I decided to pack a selection of the parts in separate bags. One of the bone parts I packed in a sealed tube. Later on my return, all the parts were packed separately in ziplock bags. The bone part was packed in a sealed hard container throughout the trip. I took film recordings and photos throughout the day, both of the items, the original place, as well as the items we encountered but did not take. I tried to document the items taken as best I could.

The Tweet

I was touched by the fact that so many things were still lying around in the area. I couldn't imagine that, if something like this happened in the Netherlands, it would be like this. I was reminded of Rutte's statement "the bottom line" and I then sent a, in retrospect, very misplaced Tweet.

To whom would I best bring a trash bag full of MH17 stuff?....

- Michel Baljet (@michelbaljet) Jan. 4, 2017

with the thought: who is still in it to get to the bottom of it or is no one in it anymore and let's leave things be. After posting the tweet I did not immediately get crazy reactions. During a broadcast of EenVandaag it became clear to me that it had been badly received by the relatives. I immediately apologized for this.

Public Ministry

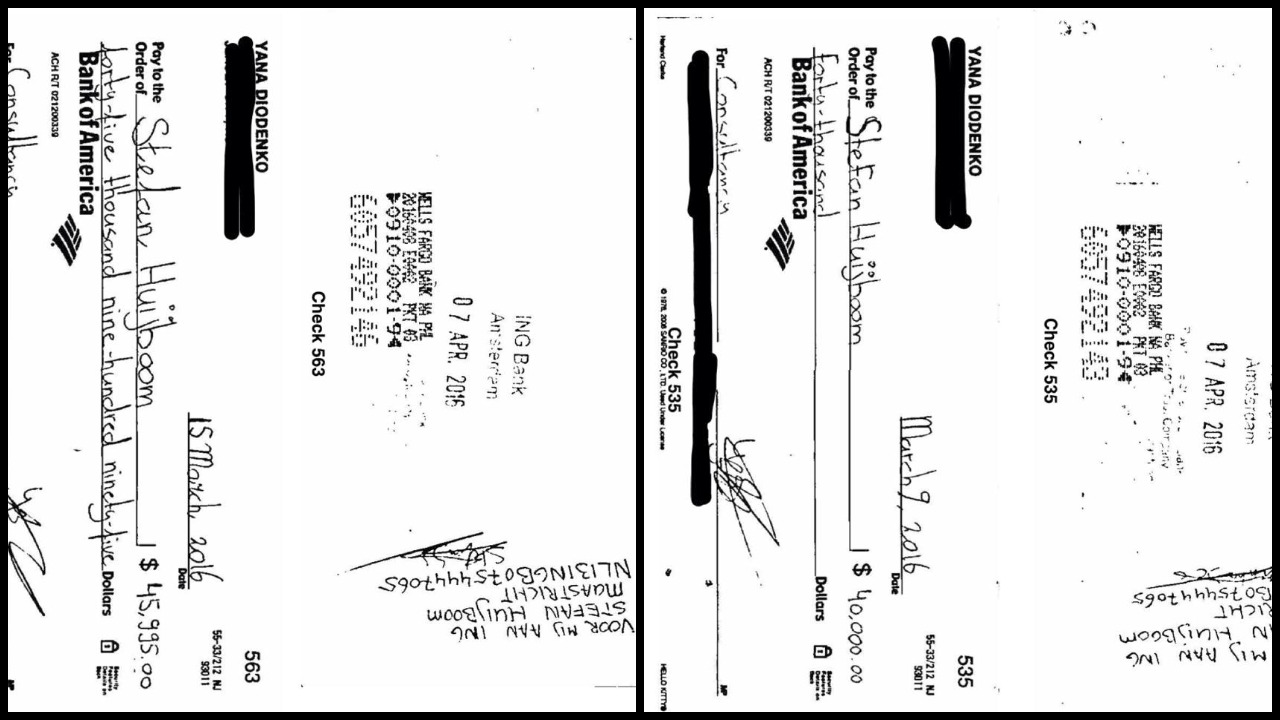

January 6, I received an email from Gerrit Thiry (Coordinating Team Leader MH17) in which he stated that he would like to be in touch with me soon "to get the items that were secured available to the investigation team as soon as possible so that forensic investigations can be carried out if required. He also warned me that under Dutch law it is a criminal offense to take items from a crime scene. On the same day I received an email from Gerrit Thiry, this was in response to an interview with EenVandaag in which I indicated that I wanted to hand over the items. He confirmed my wish in the email and gave me two options for transfer, the Liaison in Moscow or at Schiphol. Last Saturday we confirmed with each other via text message and phone that it was a voluntary transfer, not a criminal recovery. Our flight had a delay, of this I still informed him. Upon arrival at schiphol, I received a message from him that they would be ready for me at the gate.

At customs

Since Stefan was not there on the day of the visit to the crash site and he did not support me taking the bone part with me, we agreed before the flight to say goodbye firmly. Upon arrival at the gate, I was received by Gerrit Thiry and several other men including a digital forensics expert and some members of the State Police. Together we walked to the baggage belt to get the luggage. At the baggage belt, confusion briefly ensued as my traveling companion took the wrong luggage off the belt. Within a minute I managed to reach him (by phone) and took the bag from him. I then walked on with Thiry and several others to a room somewhere inside Schiphol that was reserved for us. Stefan was taken to another room; I didn't speak to him again until a day later.

In the room, even before the handover, I was asked if digital forensics expert could make an ISO (copy) of all my data. I then indicated that I was willing to hand over the images from the crash site with the understanding that any sources and conversations would be anonymized. I refused to make available all my data from the entire trip in Russia and DNR because over 90% of the data had nothing to do with MH17 and contained politically sensitive information. In addition, I also did not see the point in transferring data from my audio recorder and phone because 0% contained data from MH17. With my proposal to limit it to the data of MH17 and the crash site, the OM immediately disagreed, after which they proceeded to confiscate all my belongings. They seized from me a laptop, 3 phones, a 4k panasonic camera, a nikon d80, a small camcorder, an audio recorder, an external hard drive and several SD memory cards. My request for an attorney was denied. I did eventually get to make a phone call in their presence to notify someone.

How to proceed.

I regret how things turned out. I am disappointed in the prosecution's conduct. I also completely disagree with the press release they issued. I indicated from day one that I wanted to hand over the stuff and at no time did I abandon that thought. One can argue about ethics, but that's a whole other discussion. What is also another discussion is the way some media platforms and journalists published about this issue without reciprocity. This has created a lot of noise in recent days.

I am grateful for the support of the NVJ. A magistrate judge is currently considering the seizure. I have invoked my source protection. I assume the Judge will grant source protection, after which I am still willing to voluntarily turn over the relevant footage. The Judge's decision is expected on January 10 or 11.

To the relatives of those who perished in the MH17, I would like to apologize, both for the very lousy tweet and for the fact that old memories are being brought up. The misinformation within various media over the past few days has not helped. Should you have any questions for me, I am always available.

Update: Stefan Beck's statement stands here

(Photo: Vladislav Zelenyj)